Essex Collection of fine Taino artifacts now on exhibit at MONAH

Now on exhibit at the Museum of Native American History in Bentonville is the Essex Collection of fine Taino artifacts on loan from Jack Hart.

The Taino inhabited several Caribbean islands some 500 to 800 years ago, including Cuba, Trinidad, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico. While they developed no written language, they had a complex political, religious, and social system. They were also skilled weavers, potters, and carvers. The Taino were the first native Americans who greeted Christopher Columbus in 1492. They ceased to exist within 60 years after the arrival of the Spanish colonists.

Their incredible talents and contributions can still be seen in their artifacts. Jack Hart, a landscape architect from Florida, has loaned a collection of Taino artifacts to MONAH for an indefinite period of time.

Here is the museum’s Q&A with Hart about the collection currently on display:

About the Collection

Q: How long have you had the Taino Collection and what got you interested in the Taino story? What is the history of the collection? And where were you when you first encountered your first Taino artifact?

A: I purchased a few Taino artifacts 10 or 12 years ago. The anthropomorphic and zoomorphic imagery spoke to me, and the culture and time period intrigued me. I needed to learn more. Maybe eight years ago, another friend decided to part with some Taino artifacts that really spoke to me. The artifacts had great presence, or to me ‘mojo’. My friend called the collection, “The Essex Collection” and I thought I would carry that forward. I continued to add other groups of Taino artifacts from old collections I found, but I kept the Essex name.

Q: You have studied other Native American cultures through their artifacts. What are those cultures and do you still collect them?

A: After a trip to the Santa Fe area, I began to collect Southwest artifacts– Anasazi , etc. over 20 years ago. I then became friends with Kevin Pipes, and turned to Mississippian, Caddo and Quapaw pottery at a time when Kevin was buying some large collections and he allowed me to be an early picker. Also, these cultures were closer to home as I then lived in Charleston for about 30 years. Through attending artifact shows, I eventually befriended Dave Walley among others and got the bug to collect Pre-Columbian pottery south of the border. That opened a whole new and much larger world to explore and learn about the many cultures involved, and there are many!

Finally, the Taino culture became my primary interest over the past five years. I recently moved to Cali, Colombia with my Callana spouse and our second grade school children. Recently, I have sold off the majority of my collections and I have only kept a minimum of pieces from which I can’t bring myself to part with. At this time, the Essex Collection is the exception and my plan is to keep it intact.

Q: What makes you move on to a new culture?

A: The pursuit of knowledge, but also, sometimes it can simply be the pursuit to acquire great pieces of art– the chase. I don’t collect modern art. I don’t really understand it. But prehistoric art fascinates me. It is mysterious, it lacks much of a written record, and requires thought and conjecture by the individual admiring these artistic creations by early man. What was he thinking and how were his thoughts influenced in order to create such advanced and beautiful works of art?

Q: What attracted you to the Taino culture? Is there something powerful in the location that drew you to their story?

A: The art speaks to me– the “mojo” of the art. The “Zemi’s” are powerful expressions, primarily religious in nature, impressions of ‘gods’ who oversee their daily lives. To know that the Taino were the first peoples to interact with the discovery of the “New World” and to also know in the written record that they were decimated because of this chance meeting is also a powerful incentive to learn more about Earth’s early exploration. And later, maybe help explain and understand the ongoing migration of human civilization.

Q: The Taino are known for being the first Native Americans who met Columbus. They disappeared shortly after. What are your thoughts about what happened to the Taino people?

A: The coming of the Europeans, the discovery of the new world, ended up being a travesty for the native populations. The first to be commandeered were the peoples of what is now the Dominican Republic where Columbus first landed in his westward voyages. According to the journals and in his own words, he met a peaceful and gentle people, but over a short period of time he and his followers enslaved them and soon annihilated the population through torture, hard labor, and disease in a short time. The survivors fled to the countryside and in particular the mountains. They hid out, away from the Spaniards and practiced their own beliefs as they could. They fled disease and oppression, eventually intermarrying with slaves from Africa brought to take their place as slaves in their absence, and became the peoples of the Dominican Republic today whom many still claim their ancestry as Taino.

Q: Do you have a personal favorite artifact on display at MONAH? Why is it your favorite and how important is it to your collection?

A: I am enamored with all the artifacts (Maybe it’s a psychological disease?! Collecting! Hope that’s a joke.)

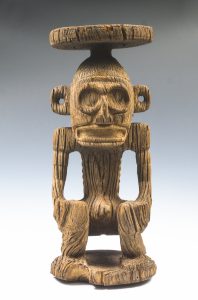

The seated wood shaman really speaks to me, and also the Macorix Head. Both are extremely well made and proportioned. They were made by masters. The shaman is a very rare piece; possibly one of a kind, as the only other equivalent / comparison I am familiar with is in clay.

The Macorix head is also a one of a kind, very detailed and with additional features not usually extended in the same image. The Macorix people were a separate population, living in a different coastal region in the Dominican Republic from the Taino, but contemporaneously with the Taino. According to some Colonial journals, they did not communicate very much, as their language and probably customs were not the same. But without doubt, I see close ties in their art to the Taino.

Q: What do you foresee as a future for the Essex Collection?

A: I would like to see the collection in a permanent museum display, and open to the general public where this art can be seen, appreciated and elicit wonder with the pursuit of further knowledge and study by the viewer.

Q: Has this collection been on public display before?

A: The two larger stone figures were part of a larger European exhibition from the Cooper Royer Collection. These two pieces are also published in “Tainos People d’amour by Bernard Michaut, 2007. One of the Wood Cohoba stands was exhibited in Miami, I believe through the Lislak Foundation, in 2003. I believe the majority of the Essex Collection has not been published or on public view. The Museum of Native American History is really the unveiling of this Collection.

Q: Some of the items on display were used for the Cohoba ritual. Could you give us a brief description of this ritual?

A: The Cohoba Ritual was performed by the Shaman (Behique) and sometimes by the Behique in conjunction with the cacique (Chief) dependent upon what was to be addressed, the healing of a person with sickness, questions to be answered by the ‘gods’ for problems with the crops, new lands, neighboring tribal altercations, and so forth. The entire local settlement that was ruled by Caique, or perhaps only the person and the direct family of a person with the sickness might attend said ritual ceremony. The ritual began with the Behique and sometimes with the Cacique –first fasting, possibly for a long period of time. Next they would purge themselves (induce vomiting) with the use of a highly decorated ‘vomitivo’ stick– made of wood or bone, as a mode of ritual cleansing in preparation to enter the spiritual world. Then by snorting / inhaling the prepared and crushed seed of the Anadenanthera Pergrine or Piptadenia Pergrine tree, (aka , Ligna vitae, Guayacan official or Guaiacum sanctum, or sometimes use of the common name ‘Ironwood’) which is one of the most potent hallucinogens indigenous to the ‘New World’. This was sometimes mixed with tobacco or crushed shell. Said ‘leaders’ would then go into a hallucinogenic trance in order to interact with the super natural world. They would use cohoba to contact the spirits, and to speak with the Zemis, for help in determining the cause of illness and also to help in determinations of what is to be done to solve important questions or problems.

During this ceremony, they would be seated on their usually ornate Duho (Low seats or chairs). This would give them some elevation above the surrounding subjects. The Duho was probably painted with colorful mineral dyes. They would then take their Cohoba powder from a highly decorated Cohoba bowl, possibly with a highly decorated Cohoba spoon and place the powdered Cohoba mixture onto decorated stone –Cohoba stand or an Cohoba snuff tray– and then partake and inhale / snort the powder. They would then sit motionless for some time, enter a trance like state, and when they emerged from that experience –they could tell their journey, their visiting the Zemis and tell of their ‘gods’ recommendations for their future.

This would seem to be one instance of how the Cacique as well as the Behique had some authority and control over their immediate population or settlement. This ritual authority helped keep the Cacique as well as the Behique in power, and as leaders of the pack. Without political organization, chaos will ensue.